Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that causes the body to attack healthy tissue. According to WebMD, lupus affects women way more than men, with 90% of lupus cases being women.

It can affect the individual with varying degrees of severity ranging from mild discomfort to lifelong disability.

It can be triggered by different environmental stimuli including light exposure, and it is this correlation between light exposure and flare-up that a team of researchers at University of Minnesota Twin Cities have used 3D printing to address.

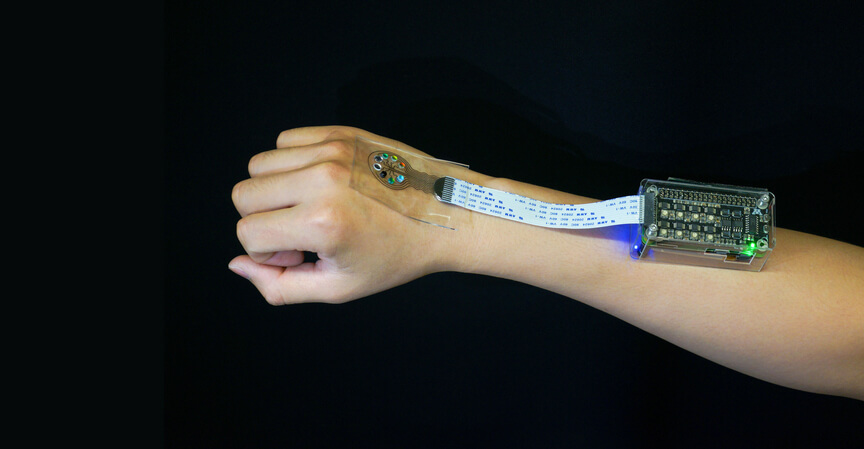

The printed wearable device, seen in the image below, provides real time monitoring of light exposure and the condition of the skin in real time. It can therefore be used to monitor any correlation between light exposure and flare-up, and can potentially be used to warn the wearer when an attack is imminent.

40 to 70 percent of people with lupus have sensitivity to light and find that internal light, external light, or both, can cause flare-ups from the condition.

Flare-up symptoms include fatigue, rashes, and joint pain.

“I treat a lot of patients with lupus or related diseases, and clinically, it is challenging to predict when patients’ symptoms are going to flare,” said Dr. David Pearson, dermatologist at University of Minnesota Medical School.

“We know that ultraviolet light and, in some cases, visible light, can cause flares of symptoms—both on their skin, as well as internally—but we don’t always know what combinations of light wavelengths are contributing to the symptoms.”

To facilitate development of the wearable device, Pearson turned to the mechanical engineering department at the university, and employed the assistance of Professor Michael McAlpine and his research group. The mechanical engineers developed both the 3D printed wearable segment and also the flexible UV-light detector.

The device is integrated with a custom-built portable console to continuously monitor and correlate light exposure to symptoms.

“This research builds upon our previous work where we developed a fully 3D printed light-emitting device, but this time instead of emitting light, it is receiving light,” said McAlpine, who was also a co-author on the published paper.

“The light is converted to electrical signals to measure it, which in the future can then be correlated with the patient’s symptom flare ups.”

The 3D-printed portion comprises multiple layers of materials printed on a biocompatible silicone base. The layers include electrodes and tunable optical filters. The filters can be designed to assist with the detection of different wavelengths of light.

You can see part of the printing process in the video below.

Asides from lupus, the system could prove to be useful to sufferers of other light-sensitive conditions. The combination of low-cost manufacturing and customizability could provide access to a data driven approach to medicine for many people.

“There is no other device like this right now with this potential for personalization and such easy fabrication,” said Pearson.

“The dream would be to have one of these 3D printers right in my office. I could see a patient and assess what light wavelengths we want to evaluate. Then I could just print it off for the patient and give it to them. It could be 100 percent personalized to their needs. That’s where the future of medicine is going.”

Approval to begin testing the device on human subjects has been granted, and will soon commence with enrolment.

The full paper, titled “3D Printed Skin-Interfaced UV-Visible Hybrid Photodetectors,” is available for your perusal (open access) over at the Advanced Science website.