Over the last year we have seen wider adoption of AM processes for use in repairing items, particularly in the marine and aerospace sector.

Sometimes companies make parts so complicated and expensive that it’s simply not economical to make a new part from scratch or to repair it with traditional means (normally cutting/machining and welding).

To that end, AM processes ranging from LMD to Cold Spray have demonstrated their worth here, where engineers are seeking to add just a bit of new material to their existing metal parts rather than printing the whole part anew.

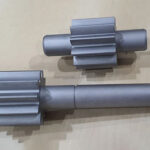

Recently the Australian submarine fleet has been getting the restorative AM treatment by employing the cold spray AM process in the in-situ repair of components on their Collins Class submarines. You can see one of those in the picture below.

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) has 6 of the locally built submarines in their fleet, and they have recently been given a $10 billion refit to upgrade the aging fleet as it approaches the end of its 30 year service life.

They were initially constructed by the Australian Submarine Corporation (ASC) and it is the ASC who are taking charge of the refits and the development of the additive manufacturing workflows. ASC has partnered with CSIRO and DMTC Limited to further develop cold spray technologies for the repair of metal surfaces and to perform in-situ repairs on the submarines

“It’s vitally important for ASC to be on the cutting edge of submarine sustainment innovation, to continually improve Australia’s submarine availability to the Royal Australian Navy service,” said Stuart Whiley, CEO at ASC.

“The use of additive manufacturing for the repair of critical submarine components, including the pressure hull, will mean faster, less disruptive repairs for our front line Collins Class submarine fleet.”

Ultimately, performing repairs out at sea will reduce time needed docked at land for repairs and will increase the operational efficiency of the submarine fleet.

Cold spray works by injecting metal powder into a supersonic stream of gas, which carries the powder particles onto the surface being repaired. The particle hits the surface with a high kinetic energy and undergoes plastic deformation at the impact site, gradually building up material in that area over each pass of the toolhead.

Obviously these machines are quite big, so ASC are particularly focused on the task of making a more portable version of the cold spray AM machine for use on the subs. They are doing this with the assistance of CSIRO at the Lab22 AM research centre in Melbourne, continuing on a path of cold spray innovation which CSIRO has apparently been on for a while.

“CSIRO and ASC have been working together for a number of years, exploring ways to use cold spray of nickel to repair corrosion,” said Dr Peter King, Research Team Leader at CSIRO.

“CSIRO has spearheaded the adoption of cold spray by Australian industry since first introducing the technology 18 years ago. We have developed unique cold spray-based solutions for the printing industry, aerospace, rail and for combating marine biofouling.”

It seems the RAN is in good hands with CSIRO, and the AM workflows along with the 10 billion dollar life extension program should see the submarines carrying on their operations efficiently into the 2030s at least.